This might seem like an strange title for a blog focusing on photography but, to be honest, it is question that almost every photographer will grapple with at some time or another.

Robert Adams, one of the illustrious photographers associated with the New Topographics movement, once wrote, ‘For photographers, the ideal book of photographs would contain just pictures - no text at all.’ He is definitely a photographer of a similar mind to Seamus Murphy (even if their photographs could not be more different).

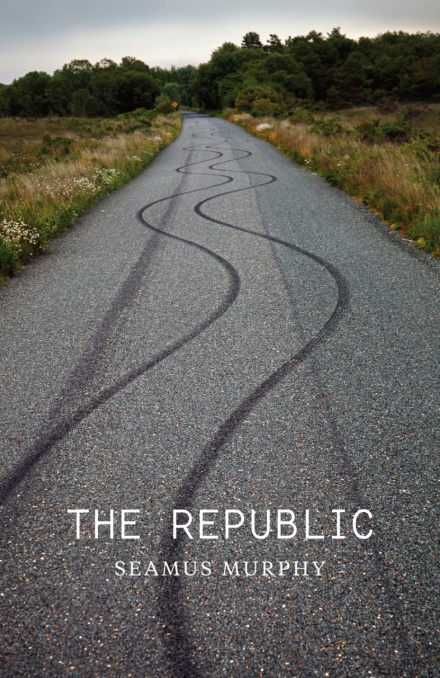

I recently got my hands on a copy of Murphy’s book, The Republic, a lyrical photographic depiction of his home, the rapidly changing Ireland. What immediately stood out for me is the lack of any contextualising information. While there is a short quote by James Joyce to introduce the images there are no captions to accompany them and an all too short (in my opinion) afterword by Murphy.

So what does this mean? Everything and nothing. It is a powerful and fascinating depiction of an old, conservative country becoming a young, liberal country. It is full of humour and life. It is a very accomplished collection of images. I just wonder if it gets as under the skin of Ireland as it could if it had explanatory captions?

As an example I’d like to look at the image above. It is definitely one of my favourite images from the book. Through research I have found out that it was taken at the Pantibar, one of Dublin’s best known gay bars, and was taken in the months leading up to the historic referendum about the legalisation of same sex marriages. In a country with the conservative, Catholic history that Ireland has this is a striking picture of modern Ireland. Yet, I only know this because I spent some time researching this particular image.

David Goldblatt, the late, great South African photographer, once said he regarded captions, and sometimes even extended captions, to be integral with the photograph. He was a photographer that saw the world as such a nuanced and layered place that an image might not be able to convey the meaning that he as the photographer had encoded into it.

In an interview with Baptiste Lignel, Goldblatt talked further about this view when Lignel asked him how it would change the meaning of his book, In Boksburg, if all the text had been taken away. For this book Goldblatt photographed everyday life in Boksburg, a perfect example of suburban white South Africa. At times it draws an almost idyllic image of life at the time in South Africa, full of sunshine, open spaces and middle class opulence. Yet, these images were created during some of the darkest years of apartheid.

Saturday afternoon in Sunward Park, Boksburg, Transvaal

Funeral with military honours for two boyhood friends who went to school together in Boksburg, were drafted into the same unit of the South African Army, and were killed in the same action against SWAPO insurgents on the Namibia-Angola border, Boksburg cemetery

I chose these particular images to illustrate Goldblatt’s use of captions. Which, while always formal, focus on describing those details that are impossible to capture in the image such as where and when the lawn is being mown and the story of the two boyhood friends whose funeral he photographed. These details might well be known by some but for outsiders they would certainly not be.

Goldblatt felt that South Africans, depending on their age and background, could be forced to speculate about the subject of some of the pictures but if they had knowledge of South African middle class life and the race relations at the time, that they should have a good sense of what the work is about. He did worry that outsiders, perhaps people from foreign countries without the same experiences, would associate the images with their own experiences and could possibly miss out on the more subtle, textured meanings surrounding what he called the “legistlated whiteness of ‘our’ milieu.”

How does this all come back to The Republic? Well, I can’t help but wonder how much more I would like the book if it was more contextualised? As an ‘outsider’ I wonder how much nuance is passing me by? I keep going back to the earlier image taken in the Pantibar. How would an outsider from a liberal country encounter this image? I can’t help but feel that Goldblatt was right and that they would interpret it through their own learned liberal experience as little more than a well framed and lit image of people out having fun. How many other images have I misinterpreted or not even bothered to interpret throughout this book through a lack of context?

While there is a truism in photography that says one can never control how one’s audience encounters or, even, interprets one’s images. I do like to think that through the use of contextualising texts such as captions and introductions or artist’s statements one has a much greater chance of doing this.

Books consulted: